Last week I did an introductory sermon to a new sermon series on the Parable of the Prodigal Son.

As an aid to exploring this parable in greater depth I will be using a book written by Henri Nouwen called “The Return of the Prodigal Son”. The book in turn is a reflection on Rembrandt van Rijn’s painting by the same name, a painting that Rembrandt painted very near the end of his own turbulent and tumultuous life.

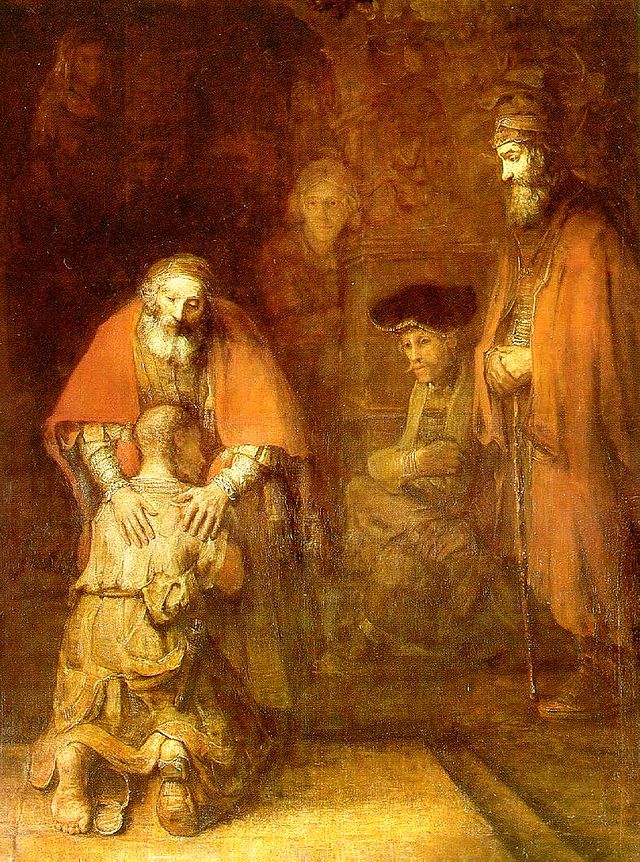

As I shared last week, the painting by Rembrandt is a beautiful and moving depiction of the moment the prodigal son meets and is embraced by his father when he returns home. The kneeling son rests his face onto the father’s chest as the elderly and partially blind father places his hands gently over the son’s shoulders as he receives the lost and now destitute son with warmth and tender love, back to himself.

There is a beautiful stillness to the painting, almost as though Rembrandt has captured a moment of eternity on canvas. Henri Nouwen suggests that this painting reveals how by the end of his life, an inner transformation had taken place, with a deep sense of having developed an inner vision and a spiritual insight that he did not have in his younger years.

Henri Nouwen writes that in Rembrandt’s younger years, Rembrandt had all the characteristics of the prodigal son. He was… “brash, self-confident, spendthrift, sensual, and very arrogant.” Henri Nouwen writes that at the age of 30 Rembrandt painted himself as the lost son in a brothel, with his wife Saskia painted as one of the ladies of the brothel.

Rembrandt painted himself with his half-open mouth and lustful eyes holding up a half-empty glass while with his left hand he touches the lower back of the girl who appears to be seated on his lap.

It is a portrait of merriment and sensuousness, that perhaps captures something of the character of Rembrandt in his younger years.

Henri Nouwen writes that all of Rembrandt’s biographers describe him as a proud young man, strongly convinced of his own genius and eager to explore everything that the world has to offer; an extrovert who loved luxury and was quite insensitive towards those around him. In addition, like the younger son in the parable, one of Rembrandt’s main concerns was money. Rembrandt made a lot, spent a lot and also lost a lot. Nouwen writes that a large part of Rembrandt’s energy was wasted in long drawn-out court-cases about financial settlements and bankruptcy proceedings.

Nouwen writes that other self-portraits of this period reveal Rembrandt as a man hungry for fame and adulation, fond of extravagant costumes, preferring golden chains to the traditional starched white collars, and sporting outlandish hats, berets, helmets and turbans.

After Rembrandt’s short period of success, popularity and wealth as an artist what followed was a period of much grief, misfortune and disaster. He lost 3 children over a five year period from 1635 – 1640. Two years later his beloved wife Saskia died in 1642. After her death he had an affair with a women he had hired to look after his nine-month-old son Titus, which ended in disaster.

After that disastrous period of his life he had a more stable union with another women, Hendrickje Stoffels who bore him a son who died in 1652 and a daughter, Cornelia.

Henri Nouwen writes that during these years, Rembrandt’s popularity as a painter plummeted and in 1656 Rembrandt was declared insolvent, having to sign over all his property and effects for the benefit of his creditors in order to avoid complete bankruptcy. In doing so he lost all of his possessions, all of his own paintings as well as his collection of other painters' works, his large collection of artefacts, and his house in Amsterdam with all its furniture.

When Rembrandt died in 1669, he had become a poor and a lonely man. Only his daughter Cornelia, his daughter-in-law Magdalene van Loo and his granddaughter Titia survived him. His common law wife, Hendrickje had already died 6 years earlier and his son Titus had died a year before his own death.

And yet, rather than becoming bitter and twisted by this tumultuous life; rather than wallowing in his own pain and self-pity, this life of excess, leading to disaster and loss had a purifying effect on him. In a way his life of ruin and loss led him in a movement away from the glory of the world that seduces with all its glittering lights to a discovery of the inner light of old age, the glory that is hidden in the human soul which surpasses death. While his own story had begun in excess and waste like the prodigal, in a very profound way, it was that very journey that led him to the Inner Light of God’s grace and compassion that is expressed so profoundly in his painting of the Return of the Prodigal Son.

In a way, by the end of his turbulent life, Rembrandt had indeed become the prodigal who was now ready to return Home to God. In a very real sense, the prodigal son depicted kneeling before his father is a depiction of Rembrandt himself. It was he who had learned by the end of his life how to kneel before the God who had made him and loved him, it was he whose pride and brashness had been transformed into humility and surrender before the tender Love of the Divine.

But in another sense, Henri Nouwen suggests that Rembrandt was not only the younger son in this painting returning home to the father. In a very real sense, by the end of his life, Rembrandt had indeed grown to become also the gentle, welcoming, tender father depicted in the painting. The only reason that Rembrandt could the gentle compassionate embrace of the father was because that gentle wisdom and compassion of the father had begun to dwell within himself as well. Nouwen writes: “One must have died many deaths and cried many tears to have painted a portrait of God in such humility”.

At the end of his life he was indeed the prodigal who had begun to find his way home to God, but in another sense the gentle, loving and welcoming father had come to dwell within the sanctuary of his own heart.

The journey of the Protestant, Reformed painter, Rembrandt Van Rijn from being the prodigal son in his youth to somehow also becoming the father in the parable by the end of his life, is, in a different way, paralleled in the life of the Dutch Catholic Priest Henri Nouwen whose life had become so deeply affected by Rembrandt’s painting.

As I shared in last week's sermon, when Henri Nouwen had first encountered the painting, it was the prodigal son that had so captivated his attention. He had realised that he was that son. He was looking for a place he could call home. He was the one who felt lost and longed to be embraced.

But a few years later, while discussing the painting with a trusted friend in England, his friend had looked quite intently at Henri and said, “I wonder if you are not more like the older son?” With those words, his friend had opened up a new space within him. He had never thought of himself as the older son, but the more he thought about it, the more he realised that there was indeed an older son living within him. He had always lived quite a dutiful life, just like the older son, When he was 6 years old, he already wanted to become a priest. He was born, baptised, confirmed and ordained in the same church. He had always been obedient to his parents his teachers, his bishops and indeed to God. He had never truly run away from home and had never wasted his time and money on sensual pursuits, and never gotten lost in debauchery and drunkenness. For his entire life he had been quite responsible, traditional, home-bound. And yet for all that he may well have been just as lost as the younger son in the story as he saw himself in a while new way. He writes: I saw my jealousy, my anger, my touchiness, doggedness and sullenness, and, most of all, my subtle self-righteousness. I saw how much of a complainer I was and how much of my thinking and feeling was ridden with resentment. I was the elder son for sure, he writes, but just as lost as his younger brother. I had been working very hard on my father’s farm, but had never fully tasted the joy of being at home.

Having first identified himself with the younger son in the painting, and then discovered that he was the elder son for sure, a few years later, he became challenged by another trusted friend, who again, when reflecting on the painting with him said to him, “Whether you are the younger son or the elder son, you have to realise that you are called to become the father… You have been looking for friends all you life; you have been craving for affection as long as I’ve known you; you have been interested in a thousand things; you have been begging for attention, appreciation, and affirmation left and right. The time has come to claim your true vocation – to be a father who can welcome his children home without asking them any questions and without wanting anything from them in return”.

In writing his book on the Return of the Prodigal Son as few years after this conversation, Henri Nouwen writes: I still feel the desire to remain the son and never grow old. But I have also come to know in a small way what it means to be a father who asks no questions, wanting only to welcome his children home.

Over the next few weeks, may we also discover within ourselves not only the lost children of God, but also the compassionate mother and father that is God. Amen.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed